|

-- carmelite ngo reflection paper --

|

||

|

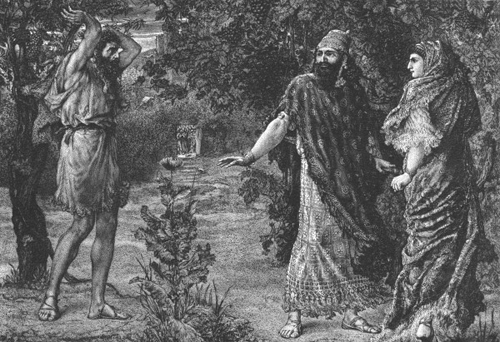

Murdering Naboth: So [Jezebel] wrote letters in the name of Ahab and she sealed them with his signet and sent the letters to the elders and nobles who were living in Naboth’s city. 1 Kings 21:8 The role that the elders, nobles and villagers of Naboth’s hometown play in the plot against Naboth’s life is a seemingly minor detail in the account of Naboth’s vineyard, though, upon closer inspection, it is as disturbing as it is instructive. The presence of those leaders and townsfolk shatters the dualistic categories that would reduce this episode to a story about good guys and bad guys or cops and robbers–a story that pits mean old Jezebel against saintly Elijah and thus allows me to remain in the shadows as Naboth is stoned to death.

I

am tempted toward this simplistic reading of the Naboth story that makes

Jezebel the villain while I, the Carmelite, identify myself with Elijah,

pretending to play the prophet at the beginning of the third millennium as

I cloak myself in Carmelite rhetoric that would usurp the contemporary

theology of prophecy to describe the role of the Carmelite Order in

contemporary society. In fact, my own life more closely resembles that of

the villagers in Naboth’s town. Naboth’s Story Naboth had a vineyard situated beside the king’s palace, sort of like owning property next to 10 Downing Street, the White House, or Rome’s Quirinal Palace. Perhaps King Ahab did not approve of the strategic location of this vineyard, though neither he nor the narrator suggests that this is what motivates his desire to acquire Naboth’s property. He plans to convert the vineyard into a vegetable garden–a rather trivial, if not silly, reason to be sure. The king of Israel offers Naboth a better vineyard at a different location or a cash settlement. Not a bad deal from a king who probably could have expropriated the land next to his palace for security reasons. But Naboth won’t sell. The land has been in his family for generations and he intends to keep it. Ahab’s reaction is most unkingly. Without further negotiations or royal threats he takes to his bed, turning his face to the wall and refusing to eat. The scene is comical: a king pouting in his bedroom because his neighbor refuses to relinquish his vineyard so he can plant vegetables in it. Ahab looks ridiculous. Perhaps we are meant to laugh at him—though our laughter is short lived. Enter Jezebel. She orders the weepy king to get up and eat, assuring him that she can secure that vineyard for him. The king does not respond; he does not inquire as to what she intends to do. Even after she collects Naboth’s property, he makes no query as to how she obtained it. The modern retelling of the story reviews Jezebel’s scheme, Naboth’s murder, the transfer of the vineyard to King Ahab and, finally, the climatic arrival of the prophet Elijah. The role of the leaders and villagers in Naboth’s hometown is easily ignored. Jezebel could have hired an assassin to murder Naboth and then quietly expropriated his vineyard for the crown’s use. Then there would have been no need for the elders, nobles and villagers. Instead, the biblical text ensures that I observe their collaboration:

The men of

his city, the elders and the nobles who lived in his city, did as Jezebel

had sent word to them. Just as it was written in the letters that she had

sent to them, they proclaimed a fast and seated Naboth at the head of the

assembly (1 Kings

21:11-12). The Elders, Nobles and Villagers of Naboth’s Town Queen Jezebel, using the king’s signet, sends a missive to the elders and nobles in which she outlines her scheme. Achieving Naboth’s elimination will require several steps:

1. Proclaim

a fast. The first step in Jezebel’s scheme is to invent a crisis. In the Hebrew Bible, the proclamation of a fast suggests that human sin has set the community’s relationship with God out of joint. David fasts as an act of penance after his tryst with Bathsheba (though his servants think he is fasting for the gravely ill child that Bathsheba has borne), hoping that his penance might spare the child’s life (2 Sam 12:16). When the people of Israel worship the Baals and Astarte’s, the prophet Samuel orders a fast to demonstrate that the Israelites are ready to set right their relationship with God (1 Sam 7:6). So Jezebel instructs the elders and nobles to proclaim a fast. Of course, this is a bogus fast, but the villagers don’t know it–only the elders and nobles do. So they fast, worried that their relationship with God has been ruptured and needs to be set right. They need to ferret out the culprit who has provoked God. The elders and nobles know that Naboth is an innocent victim. During this fraudulent procedure against him, any one of them could have spoken up: “I declare that Naboth did nothing wrong. Queen Jezebel has plotted his murder!” Why did they collaborate with the queen’s plans? Potential explanations are disconcerting. Perhaps they wanted to be nice to Jezebel. Being nice to the queen could have its advantages; they could gain a favourable eye from the crown with regard to their own requests. In the future, when they need someone eliminated, they will be able to count on the queen’s support and so Naboth is expendable in the service of their social, political or economic interests. Their critical reflection is deadened by state propaganda as they revel in the royal benefits gained by executing Jezebel’s will. Should the villagers, though unaware of Jezebel’s maneuvers, been wary of the capital charges brought against Naboth? Should someone have shouted out, “I have never heard Naboth curse God or the king”? “What’s going on here?” Why did they remain silent as the plot unfolded before their eyes? Were they afraid? Did they, with no basis in fact, join in the hollering as the innocent Naboth was dragged outside their city for execution? The third step in Jezebel’s procedure requires a partnership with two “scoundrels,” the NRSV’s translation for the Hebrew l[ylb ynb, bĕnê-bĕliyya>al (I think “vile opportunists” would be a more appropriate translation than the generic “scoundrels”). This Hebrew title is reserved for the worst characters in the Bible. In Deuteronomy 13, the bĕnê-bĕliyya>al urge people to worship other gods. In Judges 19 the bĕnê-bĕliyya>al rape and murder a traveler’s concubine. The corrupt sons of Eli receive this designation as well (1 Sam 2:12) because they pilfer from the sacrifices that pious pilgrims bring to the Lord at Shiloh. These are the characters whose assistance Jezebel urges the elders and nobles to solicit in order to achieve Naboth’s murder. And these town leaders agree to do so. What did they promise the bĕnê-bĕliyya>al in return for their treachery? The two vile opportunists make their charges: “Naboth has cursed God and the king.” How did Naboth react? Did he try to refute their charges? Perhaps he did, but the elders and nobles urged the wildly dangerous, unthinking crowd to shout over his voice. They needed Naboth dead. What passed through Naboth’s mind as he was dragged outside the city to be stoned? “Won’t anyone speak in my defense?” “Won’t anyone say that I never cursed God or the king?” As the stones pelted him did he realize before he went unconscious that his fellow citizens were behind this phony procedure or was he so overwhelmed by their hatred that he died in shock and bewilderment? Focusing on the role of the townsfolk brings the terror of Naboth’s murder into sharp relief. It is no longer merely a story about an evil queen and her victim. It becomes a story about the town leaders, the villagers and two vile opportunists who collaborated together to murder the innocent at the behest of the crown.

In the biblical account, Elijah confronts King Ahab just as the king arrives at his newly acquired vineyard (1 Kings 21:18). He does not mince words; he is not nice. He charges Ahab with murder and pronounces a capital sentence on him (1 Kings 21:19) and his villainous queen (1 Kings 21:23). What would Elijah have said to the criminals in Naboth’s hometown, those elders, nobles, vile opportunists and villagers? The prophet would have exposed the phony crisis that led to the communal fast, uncovering the real motivations behind it–murder and expropriation. We need not go far in our own times to uncover invented crises that have galvanized peoples to war or, in the case of the elimination of European Jewry, to genocide. The trumped up charges against the Jews in the lead up to the unspeakable horrors of the holocaust have been courageously outlined by Robert Michael in his Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust (New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2006). The threat of Saddam Hussein and his non-existent “weapons of mass destruction” provide a more recent example of an invented crisis. But such crises need not be limited to major wars on the world stage. Jezebel’s scheme is the prototype for all phony crises that are invented to achieve an unjust advantage for a particular person or group. One person invents, others cooperate, and still others quietly assist and Naboth is crushed again and again. Elijah, at the meeting of the Carmelite NGO, identifies the bogus crises in our own time and fingers those who benefit from them. The prophet hears Naboth’s voice today in the voices of indigenous peoples, undocumented workers, subsistence farmers, enslaved child prostitutes and labourers, the Roma people persecuted in western Europe and many others–the “Naboths” of our own time. The NGO Global Witness has focused international attention on the corruption of government officials in the Democratic Republic of Congo that allows the countries mineral wealth to be exploited by transnational corporations (see “Africa’s Stolen Wealth” in The Tablet, May 12, 2007). The movie “Blood Diamond” opened my eyes to the bloodshed behind the diamonds people wear. The United Nations refers to these diamonds as “conflict diamonds” (a less compelling label than the more appropriate “blood diamonds”), which it defines as “diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments.” Global Witness has challenged De Beers, the world’s largest diamond producer, on its trade in blood diamonds. Certainly Elijah would confront De Beers just as he did King Ahab. But he would also ask “the citizens of Naboth’s town” about the diamonds they wear. Is that engagement ring, meant to be an expression of love, really a witness to murder? Was that diamond mined by persons who work in life threatening conditions and are not paid a just wage? Elijah, at the meeting of the Carmelite NGO, will point out to me the subtle and often invisible ways in which I collaborate with those who exploit the working poor by enjoying the benefits of their exploitation. I, who thought myself a faithful disciple of the prophet, find myself charged as one of Jezebel’s collaborators. Elijah would demand to know from the villagers in Naboth’s town why they were silent as Naboth was murdered. What advantage were they hoping to gain? A few years back, Brian Williams, Charlie Gibson and Katie Couric, three major American journalists, were asked if the American press had failed to ask serious questions in the lead up to the war in Iraq. Both Brian Williams and Charlie Gibson hemmed and hawed: “Well, everyone thought Saddam Hussein was a threat” and “Even the Clinton administration believed he had weapons of mass destruction.” They marched out the same old answers we have heard too many times. When the question came to Katie Couric, she gave a simple “Yes.” She, as a journalist, had failed to think critically about the trumped up threat of Saddam Hussein. Her answer may not have been one that would increase her television ratings, but it was an honest answer based upon sincere, critical reflection. Individuals who refuse to obey the demands of an invented crisis can be a threat to those in power. The villagers of Naboth’s hometown chose not to become such a threat to King Ahab and his queen and so Naboth had to die. Elijah, at the Carmelite NGO meeting, exposes how I have collaborated with Jezebel. He points to the murder of Etty Hillesum, a Jewish woman who aspired to write like Dostoevsky, but was gassed at Auschwitz where her final diary entries were lost (cf. An Interrupted Life, London: Persephone, 1999). While held at the Westerbork camp (The Netherlands), she chronicled on August 2nd, 1942 the arrival of a group of “Jewish-Catholics,” “nuns and priests wearing the yellow star on their habits.” Edith Stein was among those nuns that Etty saw that day. Elijah asks me about the murders of Etty Hillesum and Edith Stein. I know who conceived the plan to murder them. But how many letters were sent to elders and nobles to obtain their collaboration in these murders? How many villagers, though not directly involved, remained silent so that Etty and Edith could be murdered? How many “vile opportunists” were hired to fabricate spurious charges against the Jews? Who enjoyed the benefits of the expropriated property of murdered Jews? At the Birkenau death camp (1.5 miles from Auschwitz), 20,000 people on average could be gassed and cremated in one day (24,000 murders per day was its maximum). This required the careful scheduling of trains, gas chambers and ovens, so that the camp would not be overwhelmed with potential victims, mostly Jews, waiting to be executed. Imagine the efforts involved on the part of many people to ensure that Edith Stein’s train arrived at Auschwitz on time so that she could be murdered on schedule. Elijah, a Jew himself, identifies the collaborators and silent observers of our own era. And I had intended to remain hidden among the villagers of Naboth’s town. Michael P. Hornsby-Smith, in his recent volume, An Introduction to Catholic Social Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), reflects at length on the role of Catholic NGOs in society: Their [the NGOs] deep involvement with deprived and excluded people and shared experiences with them give them a unique authority to challenge the vast mass of comfortable Christians with the prophetic dimension of their faith. They teach not just about charitable responses to needs but more profoundly, and indeed scripturally, about the Christian calling to break the chains of the enslavement by injustice of so many of our fellow human beings (p. 240). The Carmelite NGO, with our legendary, prophetic founder sitting at the table, challenges my comfortable Christian faith so that I recognize how, in concrete ways, I collaborate to bind my fellow human beings in the chains of injustice. Elijah will observe the suffering of “The Bottom Billion,” to borrow from the title of Paul Collier’s stimulating book (Oxford, 2008), in order to uncover my own collaboration in their oppression. Elijah might ask, “How often can members of the bottom billion see a doctor?” Then, he might turn to me, a Canadian, and ask if I recognize how my native country, Canada, benefits from the migration of educated, young professionals from the countries where “the bottom billion” live. Collier labels these professionals the “wealth” of the bottom billion countries that Europe, Canada and the United States snap up at a cheap price (the bottom billion countries provided for their education). Elijah makes me look at these modern day Naboths living in developing countries who have less access to health care so that I might have greater access. So Naboth dies while I, like one of those villagers who were just minding their own business as Naboth was dragged by for stoning, make my doctor’s appointment. The Carmelite NGO itself should not expect to escape Elijah’s prophetic glance. The prophet would note that according to the World Bank, there were approximately 10,000 NGOs in Haiti prior to the January 12, 2010 earthquake that killed over 200,000 people. That’s approximately one NGO for every 975 Haitians. What were they doing to alleviate the suffering of this people, subjugated by France to pay an equivalent of €17 billion for their liberation from slavery (The Guardian August 15, 2010)? Hornsby-Smith, at the very beginning of his book, raises challenging questions for Catholic NGOs: In practice most of the Christian NGOs in the areas of both domestic and international justice are working in strategic alliances with other Church and secular bodies. They all campaign for changes in social and economic policies in the area of their special concerns. This may retard the development of a more comprehensive understanding of unjust and sinful structures within the Christian community with the consequence that the imperative to seek the kingdom of God ‘on earth as in heaven’ fails to become a central feature of the commitment of Christians and of the Church (p. 3).

Sitting at

the table of the Carmelite NGO, Elijah will ask unsettling questions: is

the imperative “to seek the kingdom of God” central to our Carmelite

lives? Does our program to challenge others to recognize their

collaboration with injustice blind us to the unjust and sinful structures

within our own communities and Catholic NGOs (cf. Lisa Jordan and Peter

van Tuijl [eds.], NGO Accountability, Politics, Principles and

Innovations, London: Earthscan, 2006)? Welcoming Elijah Near the end of the Passover Seder, the door of the Jewish home is opened to invite Elijah to take the place reserved for him at the table. Those gathered welcome him in song: Eliyahu ha-Navi, Eliyahu ha-Tishbi, Eliyahu, Eliyahu, Eliyahu ha-Giladi. Bimhayrah v'yamenu, yavo aleynu, im Mashiach ben David, im Mashiach ben David. Elijah the Prophet, Elijah the Tishbite, Elijah, Elijah, Elijah the Gileadite. Speedily and in our days, come to us, with the messiah, son of David, with the messiah, son of David. Similarly, our Carmelite NGO opens the door to our prophet-founder and invites him to the table: “come to us, Elijah, in our days.” But this invitation is made at considerable risk. Elijah knows that Naboth’s murder was not only the action of a single individual–a mean old queen–and he will call us out of the shadows to charge us with the specific ways in which we collaborate in the murder of Naboth “in our days.” The words of the prophet must have come as a terrible shock to the citizens of Naboth’s village. His words can have the same impact on us today.

|